If someone were to show you a tree and ask the question "do you think the health of the roots affect the health of the branches and the leaves? " What would your answer be? I would say, absolutely yes. The health of the root system is imperative to the health of the tree as a whole, it’s leaves and fruit included. Not one part of the tree is separate from each other. So too with our human body there is no part that operates in isolation. Osteopaths understand the human body’s' marvellous connections and frequently draw upon the principle that everything is inter-connected when diagnosing and treating our patients.

The simple act of breathing is not simply to do with the nose, lungs and the thoracic diaphragm. Breathing or respiration is the complex dance of multiple structures which all move rhythmically in response to inhaling and exhaling. We actually have 5 diaphragms in the body that are intrinsically connected with each other and aid to move gases, body fluids and act as internal pumps to help organs work efficiently (Bruno Bordoni, 2015). The 5 diaphragms are complex structures in the body that influence each other through anatomical, fascial and neurological connections. The 5 structures are:

Tentorium cerebellum – cranial diaphragm

Cranial structures that move in relation to the respiration to regulate the cerebrospinal fluid flow

Roof of the mouth – upper cervical diaphragm

Consist of the tongue, floor and roof of the mouth, hyoid musculature.

Thoracic outlet – lower cervical diaphragm

Where many accessory breathing muscles exist to assist the airways to be open and increase the capacity of the lungs.

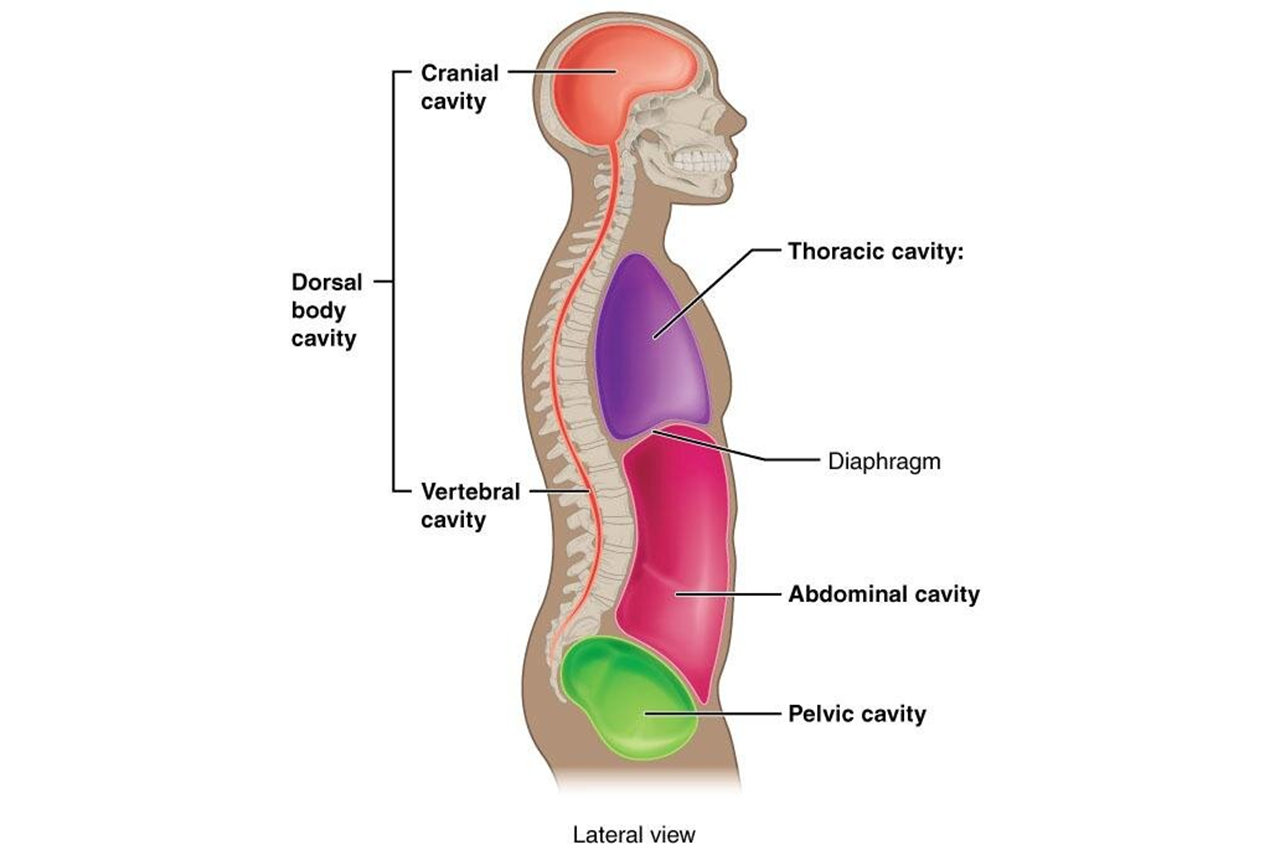

Respiratory diaphragm – thoracic diaphragm

Thin dome shaped muscle that separates the lungs from the abdominal cavity. The Diaphragm in relation to respiration descends to allow air to fill the lungs when you take a breath in and it springs back on an exhalation.

Pelvic floor – pelvic diaphragm

Pelvic floor muscles line the bottom of the pelvis aka form the pelvic bowl holding the bladder, intestines and reproductive organs. The pelvic floor descends down on an inspiration mimicking the thoracic diaphragm

When you cough or sneeze there is a direct effect on the pelvic floor from the thoracic diaphragm (Hankyu Park, 2015). When you breath in, your diaphragm descends and expands to let more air into the lungs. The increase of pressure in the abdominal cavity during an inhalation causes the pelvic floor to descend and expand. The reciprocal movement of the diaphragm and pelvic floor aid efficient movement of body fluids in the abdominal cavity and also assist in peristalsis of the gut.

The act of respiration affects the thoracic outlet where there are many accessory breathing muscles attached to the upper ribs. Chest and mouth breathing, anxiety, stress, jaw tension, poor head posture all affect the thoracic outlet causing compression of the brachial plexus causing thoracic outlet syndrome, jaw pain (temporomandibular joint i.e. TMJ pain) and headaches. Roof of the mouth and the cranial diaphragm move in relation to respiration to assist cerebral spinal fluid movement around the brain and into the brain stem affecting the whole body through the nervous system.

Why should we care?

- Osteopaths may assess you from top to toe keeping in mind the connections of the 5 diaphragms. A tight diaphragm may suggest that one or all the other diaphragms are not working optimally (Bordoni, 2020). Treating your 5 diaphragms will help balance your whole body and settle the nervous system.

- Poor breathing patterns can affect each layer of the 5 diaphragms of the body. Chest and mouth breathers tend to not expand the diaphragm which causes their midback, neck and jaw to get tight causing a host of conditions.

- Vagus nerve is the 10th cranial nerve and has a network of branches to the heart, lungs, diaphragm and gut. The classic ‘butterflies’ that you experience when you are nervous is because of the vagus nerve. Hyperarousal of this nerve from tight neck and jaw muscles, stress (release of stress hormone cortisol), dysfunctional thoracic diaphragm causes the nervous system to be in sympathetic ‘fight and flight mode’ as opposed to parasympathetic ‘rest and digest’.

(Bordoni, 2020)

3 tips to reduce tension in the 5 diaphragms

Breathing exercise

Nose breathing is beneficial to filter the air going into your lungs, more expansion diaphragm, better neck posture, reduced joint compression and muscles tension in the neck and jaw. There is research on the efficacy of mouth taping to encourage nose breathing particularly during sleep. Mouth breathers tend to have higher incidence of sleep disorders and attention deficit hyperactive disorder (Masahiro Sano, 2013).

This breathing technique can be done anywhere but make sure you are relaxed and safe.

- Take a deep breath in through your nose (5 counts). Focus on all your air going into your diaphragm/tummy and blowing your tummy up like a balloon.

- Take 2 more deep breaths in on top of the first inhalation.

- Hold that inspiration for 5-10 counts (start with 5 and then build up to 10)

- Breath it all out (5 counts) - empty your lungs and breathe 2 more breaths out on top of that. Hold for 5-10 counts

This technique can be beneficial to destress and settle anxiety allowing you to ‘rest and digest’, to clear your mind and be in the moment, to fall to sleep and as a microbreak during work hours.

Exercise and breathing

The diaphragm is a postural muscle and helps support your lower back. Ineffective breathing can lead to lower back pain over time (Regina Finta, 2018). When lifting or exercising its important to concentrate on deep breathing when warming up, during exercise and cooling down form exercise. Rushing through exercise and having incorrect technique can cause injury.

Breathing long deep breaths instead of panting away during high intensity exercise can reduce your heart rate (hence increase your fitness) and calm your nervous system.

Posture retraining

- Stand up against the wall, tuck your tailbone under and squeeze your butt cheeks

- Place the back of both arms against the wall and drop your shoulders down towards the floor

- Tuck your chin into your chest and take 5 deep nose breaths. 5 counts in and 5 counts out.

References

Bordoni, B. (2020). The Five Diaphragms in Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine: Myofascial Relationships, Part 1. Cureus, 12(4): e7794.

Bruno Bordoni 1, E. Z. (2015). The continuity of the body: hypothesis of treatment of the five diaphragms. J Altern Complement Med, 237-42.

Hankyu Park, M. P. (2015). The effect of the correlation between the contraction of the pelvic floor muscles and diaphragmatic motion during breathing. J Phys Ther Sci, 27(7): 2113–2115.

Masahiro Sano, c. a. (2013 Dec 4). ncreased oxygen load in the prefrontal cortex from mouth breathing: a vector-based near-infrared spectroscopy study. Neuroreport, 24(17): 935–940.

Regina Finta, 1. E. (2018). The effect of diaphragm training on lumbar stabilizer muscles: a new concept for improving segmental stability in the case of low back pain. J Pain Res, 3031–3045.